🌄 November Pryor Journal: An End-of-Season Look at the Pryor Range

On the Pryor Mountain Wild Horse Range with Dr. Boone Kauffman

November 2025

Cloud’s Home • Wild Freedom • Science for the Future

Arrival in Lovell: Weather, Waiting, and What Was to Come

Ginger and I arrived in Lovell on Monday, November 17th.

Overnight, the weather shifted — a mix of light rain and and snow moved across the mountains. Down low, nothing stuck, but the air felt nice - crisp and clean but not too cold. Up high, however, the range was transforming. We wouldn’t see it until later, but the top of the mountain was slowly being draped in a soft, white blanket.

A sign of winter coming.

A sign of change.

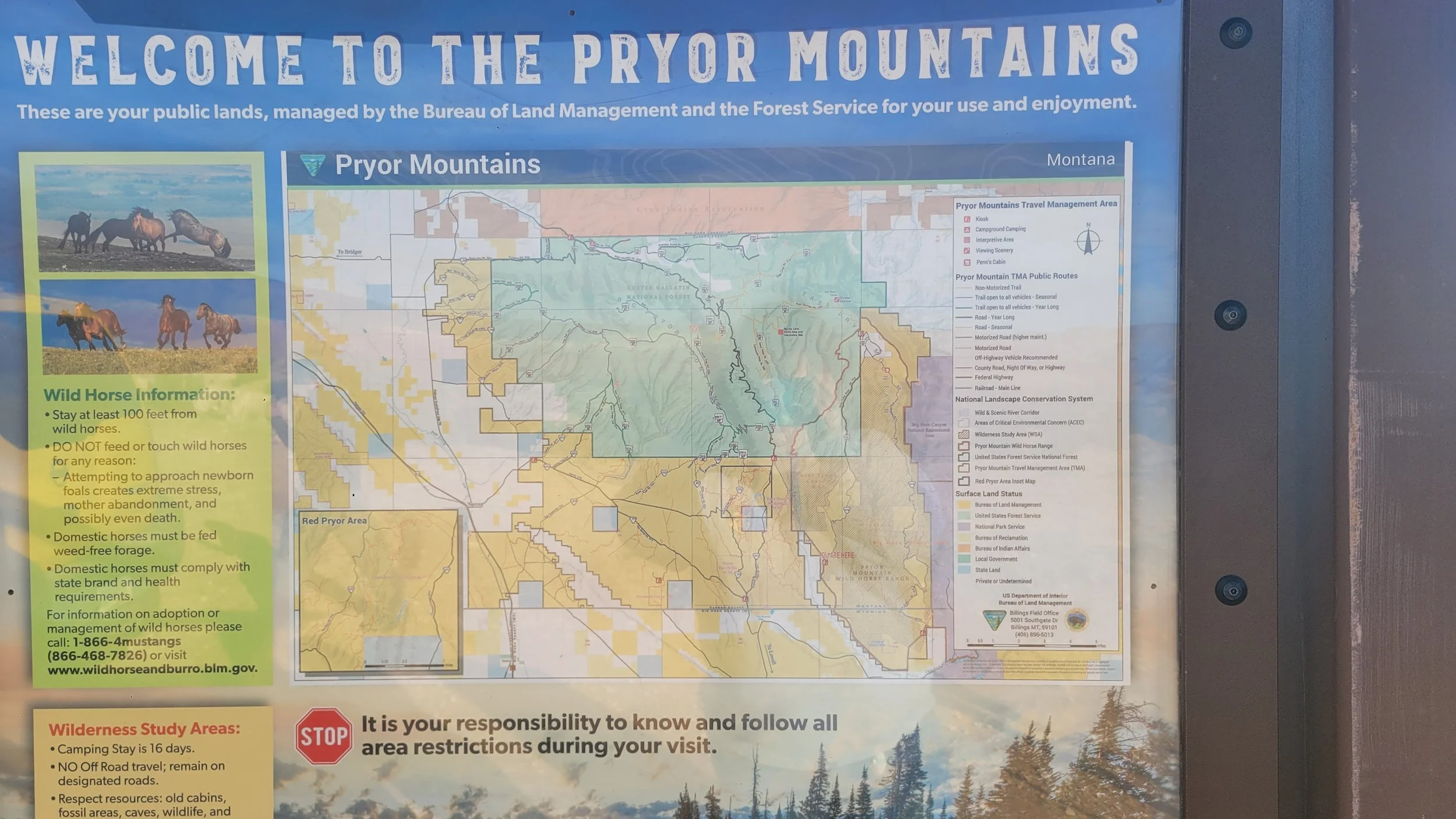

Tuesday: Picking Up Boone & the First Look at the Dryhead

We picked up Dr. Boone Kauffman mid-day in Billings. He arrived ready — eager to see Cloud’s range with his own eyes after months of preparatory reading.

Before daylight slipped away, we headed straight for the Dryhead.

The landscape there is stark and beautiful: juniper-dotted plateaus, wind-carved rock, deep silence.

We weren’t just looking for vegetation patterns — we were also, inevitably, looking for horses.

And we found them.

As we rounded a bend, I spotted Ventura first. We slowed to admire her, and to our surprise, Parry and their young colt crossed right in front of the 4Runner to join her. A perfect Dryhead welcome.

Boone’s early remarks reflected what he would later write more formally:

The Dryhead vegetation is overwhelmingly native, with only small, scattered patches of exotics, mostly along roadsides. November 2024 Pryor Mtn trip r…

That night over dinner, we mapped out the next day with Dennis McCollough, who would join us for the entire visit. Phyllis Wray had provided essential insights on where to take Boone. We agreed to start with Burnt Timber Ridge, giving Sykes Ridge one more day to dry.

Wednesday: Burnt Timber Ridge & an Encounter We Didn’t Expect

We met Dennis early and headed toward the range.

On the way, I told Boone about the domestic horse we had helped in February — the one we found tangled in the fence. I gestured to the very spot where we found him.

And then…

I saw another horse.

On the other side of the fence.

Something was wrong.

He was outside the boundary and clearly injured — his legs bloody and swollen. At first glance, it looked like he was caught in the wire again.

We turned around immediately and drove to a friend’s home to get wire cutters. Dennis and Boone stayed with the gelding.

When we returned, we learned the truth:

He wasn’t tangled in wire.

He had fallen through the cattle guard — likely trying to walk across it in the dark or in confusion. The blood on the grates told the story clearly.

His legs were badly injured.

He limped away slowly and painfully toward the hills.

We never saw his owners or anyone arriving to help him, despite them being contacted. We could only hope someone reached him. As he turned, we saw the freeze brand on his neck.

Climbing Burnt Timber: Science Comes Alive

As we continued up Burnt Timber Ridge, we stopped frequently — first along the outside of the range.

And here’s something important:

The vegetation outside the range showed no significant difference in overall forage condition compared to the vegetation inside the range.

This observation stayed with Boone.

Farther up, we inspected soils, grasses, forbs, and shrub communities. Boone would pause often, exclaiming with genuine excitement — surprised by the complexity and health of the system.

Shoshone’s Band

Below the mines, we saw Shoshone’s band foraging on the hills below us.

A magnificent sight against the rugged terrain.

The BTR Guzzler & Miguel/Miocene’s Band

We walked out to the Burnt Timber guzzler to examine conditions around the water source. There, we found Miguel/Miocene’s band, including La Brave and her very young foal, delicate and spindly-legged — perhaps only a few days old.

In the name of science (and maybe just a touch of enthusiasm), we thought Boone should take a closer look at the ecosystem in the band’s direction. to identify more plants of course. Getting a better look at the band - and the fola - was a happy bonus! :😃

Quaid’s Band & The Approach to Winter

As we climbed higher, the wind stiffened and temperatures dropped. Jackets were retrieved, zipped, and tightened. The world began towhiten in all directions as we climbed the mountain to the upper road.

We encountered Quaid’s band just before reaching the Teacup Bowl.

Later — impressively — Quaid and his band reached the upper meadows just we did, but entirely under their own power. To be fair, we did stop a few times to inspect the terrain!

Near the top, the landscape changed more noticeably:

We had definitely hit snow! Not just patches now. Not deep — an inch or two — but enough to transform the upper corner of the range into a winter postcard, especially near the road that leads toward Crooked Creek.

No horse tracks there - not even neaar the big pond.

Only coyotes had crossed the pristine snowy layer.

We continued, turning back toward Penn’s Cabin, where the snow thinned again.

Boone was astounded by the vegetation diversity, even here in November — a time when many plants are dormant and difficult to identify.

Descending at Dusk: Pride’s Band

Sunset comes early in November.

As the light faded, Dennis and Boone (traveling in Dennis’s SUV) spotted Pride and his small band tucked among the trees.

We stopped — for Pride, for the forest ecosystem, and for Boone to gather final notes on the day’s forage and soil features. The forested areas, Boone noted, are often overlooked, yet they play an essential role in the horses’ seasonal use of the range.

We ended the day exhilarated by Boone’s enthusiasm and by the things we were learning - a deeper look at the mountain ranges we enjoy exploring.

Dinner brought more planning:

Tomorrow, Sykes Ridge.

Thursday Morning: Back to the Dryhead & the Bison Legacy

Before heading up Sykes, we returned to the Dryhead to explore Mustang Flats.

Strictly for Boone’s scientific education, of course.

That Ventura, Parry, Z, Warrior King, Utopia, and Ula happened to be there was purely coincidental. (Beautiful, wild, coincidental.)

Boone explained how the native plants in Mustang Flats evolved under bison grazing, adapting to tolerate — and recover from — heavy use.

This adaptation makes the area remarkably well-suited for wild horses.

This insight appears in his written review:

“Native plant species in the Dryhead are overwhelmingly intact and adapted to grazing pressures… well suited for wild horses.”

November 2025 Pryor Mtn trip review…

Sykes Ridge: Beauty, Danger & Discovery

Sykes Ridge is not a drive for the faint of heart.

Dennis is an expert at this road, and we were grateful to ALL climb into his SUV as we headed upward.

The road winds through sharply contrasting ecosystems — desert shrublands, forest pockets, exposed ridgelines. Boone’s notebook filled quickly.

The Loss of Zephyr

At one stop, Dennis showed us where little Zephyr, a young colt we had seen in August, had been killed by a mountain lion.

The mountain reminds us: this is a wild ecosystem, whole and real.

We kept close together.

It wasn’t fear, really — just a healthy respect for a natural management system at work.

Oro’s Band

Higher up, we found Oro’s band.

They were skittish — aware of our presence — and didn’t stay long, but Boone was able to make observations nonetheless.

Time was slipping.

We chose to drive over the mountain and descend through Tillet in the dark — a beautiful, eerie ride under the stars.

Dennis headed home that night.

We were deeply grateful for his guidance, skill, and history on every road we traveled.

Friday: Mustang Center, Lower Sykes & the Final Reflections

Before Boone’s flight home, we visited the Mustang Center and introduced him to Nancy Ceroni. Their exchange of questions and knowledge was spirited and insightful.

Then back to the range one final time.

Boone wanted to see Lower Sykes — specifically Turkey Flats, an important wintering area for the mountain horses. We didn’t have time for a full hike, but even from our vantage point, Boone was struck by the diversity and structure of the vegetation.

Bachelor Sightings

At the entrance to Sykes Road, we found bachelors Hidalgo and Wyatt Earp grazing.

To our surprise, there was a fall green-up — fresh, tender grass sprouting alongside the dormancy of late autumn.

A beautiful final snapshot of the horses’ adaptability.

What Boone Saw: A Sanctuary With Incredible Potential

Across five days, Boone was consistently impressed:

Over 60 native plant species identified in November

Extremely limited invasive presence

Strong adaptation to grazing

High ecological diversity within short distances

Distinct plant communities shaped by soil, slope & elevation

Healthy winter range vegetation

High-elevation meadows with significant summer use

A mosaic of ecosystems unlike any other wild horse range

His written review concludes:

“Current ecological data is lacking, disjointed, and not representative of the Range’s diversity… A comprehensive, multi-year analysis is warranted.”

November 2024 Pryor Mtn trip r…

A Path Toward Long-Term Protection

Dr. Kauffman’s review reaffirmed something we’ve always known:

The Pryors need real science behind every management decision.

A full ecological study would require 3–5 years and cost $60–$90K per year — a significant but necessary undertaking if Cloud’s herd is to be protected with integrity and scientific accuracy.

If you know of any grant opportunities, foundations, or private trusts that support ecological research or wild horse preservation, we would be honored to have this project shared with them.

(Insert a final photo: wide landscape or symbolic image of the herd.)

Looking Ahead

Boone left the Pryors inspired — and eager to return.

We left feeling the same.

A long-term study of this range won’t be easy, but it may be the most important work we undertake for Cloud’s descendants and the future of wild horse management in America.

This mountain still has stories to tell.

And now, we have a chance to listen.