Will Public Lands Ranchers Pay More for Grazing?

Published by High Country News on March 25, 2016

By Tay Wiles

Twenty years ago, fees for ranchers grazing livestock on federal public lands were a major political issue, the subject of regular national debatesbetween conservationists and ranchers. The fee program brings in far less money for the Bureau of Land Management and Forest Service than the agencies spend on maintaining rangeland. But thanks to the power of the livestock lobby, proposals to raise grazing fees have been stymied in political controversy for decades.

Now, the Obama administration is trying again — Interior Secretary Sally Jewell has proposed an additional administrative fee of $2.50 per animal unit month (the forage needed to sustain one cow and calf, one horse, or five sheep or goats for a month).

The fee would provide $16.5 million in 2016 for the BLM — a $13.5 million net gain, considering a proposed $3 million decrease in rangeland management funding. Currently the BLM spends over seven times as much money on rangeland management and improvement programs as it collects in grazing fees; that’s $89 million versus $12 million. (The rangeland programs include things like permit administration, weed management, water development and vegetation restoration.) Income from the new fee would go toward rangeland health efforts, as well as help address a massive backlog of grazing permit renewals.

Jewell’s proposal would bump the feds’ income from grazers by 148 percent, but, because it’s a separate administrative tax, it doesn’t violate the requirement that the baseline grazing fee (for the BLM, $1.69 per AUM this year) can’t increase by more than 25 percent annually. The move, which Interior has attempted in similar forms since 2012, appears to be a last resort to get around bitter political resistance to baseline fee increases. But the attempt has been repeatedly thwarted — stripped from Obama’s budget before being passed each fall.

If the fee were to pass — an unlikely scenario, since it has to push through committee, including the Natural Resources Committee, chaired by conservative Utah Republican Rob Bishop — it would have a huge effect on Western ranchers. “If expenses for your business go up over 100 percent, that’s a big impact,” says Utah Cattlemen’s Association Executive Vice President Brent Tanner. And in Tanner's state, most ranchers use at least some federal land to graze their cattle, so would be affected by the new fee.

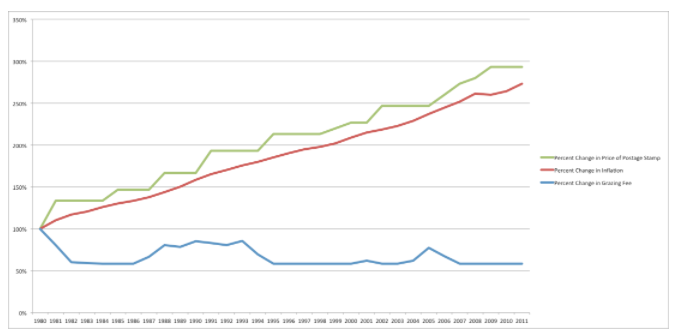

Yet conservationists have long cited the grazing fee as far too low, considering the ecological cost of livestock on public lands. The formula takes into account private land lease rates, beef cattle prices and production costs like gasoline and equipment. Thus, ranchers are supposed to pay more when conditions are good and less when conditions are worse. But that’s not what’s happened since the fee formula was implemented with the 1978 Public Rangelands Improvement Act. The rate crested the two-dollar mark just once, in 1981, and was at the legal minimum ($1.35) every year from 2007 to 2014.

Green line shows percent change in price of a postage stamp from 1980 to 2011. Red line shows change in inflation, and the blue shows change in grazing fees. Graphic courtesy Western Watersheds Project.

Grazing fees on public land were always meant to be lower than those on private land because the former often provides poorer quality forage and ranchers usually have to maintain their own fencing and irrigation infrastructure. When grazing fees were established, they were supposed to increase over time, trailing private rates. But the opposite has happened, and the gap between public and private land lease rates has increased over time. “The 2015 fee is just 8 percent of what it would cost to graze livestock on private grazing lands,” reads an economic study conducted on behalf of the Center for Biological Diversity. “In 1981, when the federal fee first went into effect, it was 23.79 percent.”

So why aren’t public land grazing fees naturally going up? That can be traced to how cattle prices and cost of production figure into the fee formula; adding these two elements to the formula did not improve its ability to predict annual forage values, says a 2001 academic paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society of Range Management. “In fact, adding these two indices ruined the predictive ability of the formula and… grazing fees have fallen further and further behind the private land lease rates through time.”

Part of the reason that grazing fees have provoked such fury from politically conservative ranchers is that they’re imposed by the federal government. And yet the BLM funnels 12 percent of its income from fees back to the states they came from. (For lands outside of grazing districts, it's 50 percent.) The rest of the income goes to a rangeland betterment fund and the U.S. Treasury. For the Forest Service, 25 percent goes back to the states and 50 percent to rangeland betterment.

Graphs from Congressional Review Service report "Grazing Fees: Overview and Issues," 2012, by Carol Hardy Vincent. Chart on the left is for lands within BLM grazing districts for which the BLM issues grazing permits. Graph on the right shows allocations for fees collected from lands outside districts.

Some conservationists, like John Horning from WildEarth Guardians, think that working with ranchers to retire grazing permits altogether may be a more realistic way to protect rangeland health than increasing fees, which at the moment, is a political non-starter. “There are two things that have eclipsed (the grazing fee debate)," Horning says, "the public lands movement, which is all about acres of protection; the second is climate change. Grazing is just barely on the radar.”

---

Tay Wiles is the online editor at High Country News.